All Aboard

The United States has a strange relationship with train travel. The first transcontinental railroad finally helped connect the enormous amount of land our government had purchased or stolen as colonists made their way westward. Trains united our states, but passenger rail is inefficient or irrelevant now in most of our cities outside of the Northeast.

America was built for cars, and there’s not much national political enthusiasm for prioritizing mass transit instead of space for personal vehicles. For the most part, we are stuck with the rail infrastructure that we have, which is cobbled together, outdated, and inefficient. It isn’t just that the United States lacks high-speed rail; it’s that we are running slow-speed rail.

This is where my friend, Nolan Hicks, is stepping in with suggestions. Nolan, a longtime NY Post City Hall and transit reporter and a current investigative reporter at Streetsblog, has been working since last summer on a radical project that examines the history of the United States’ railroad infrastructure and what can be done to get the most out of what we’ve already got.

Over the last year, Nolan has created a how-to guide for transit systems that want to join the modern age — as best as they can. Working with NYU’s Urban Management department, Nolan has put together a beautiful 155-page guide to train modernization. The official title of this report is “Momentum.” In our urbanist group chat, we’ve been calling it the “Choo Choo Book.”

“The infrastructure framework — Momentum — speeds travel with a four-pronged attack on ‘‘dead time,” writes Nolan. “That’s the cumulative time penalty incurred at each stop for deceleration into the station, boarding and disembarking, and then reaccelerating back up to speed. Modeling shows that full implementation can shorten commutes by as much as 29% and slash an hour or more off of many inter-city services.”

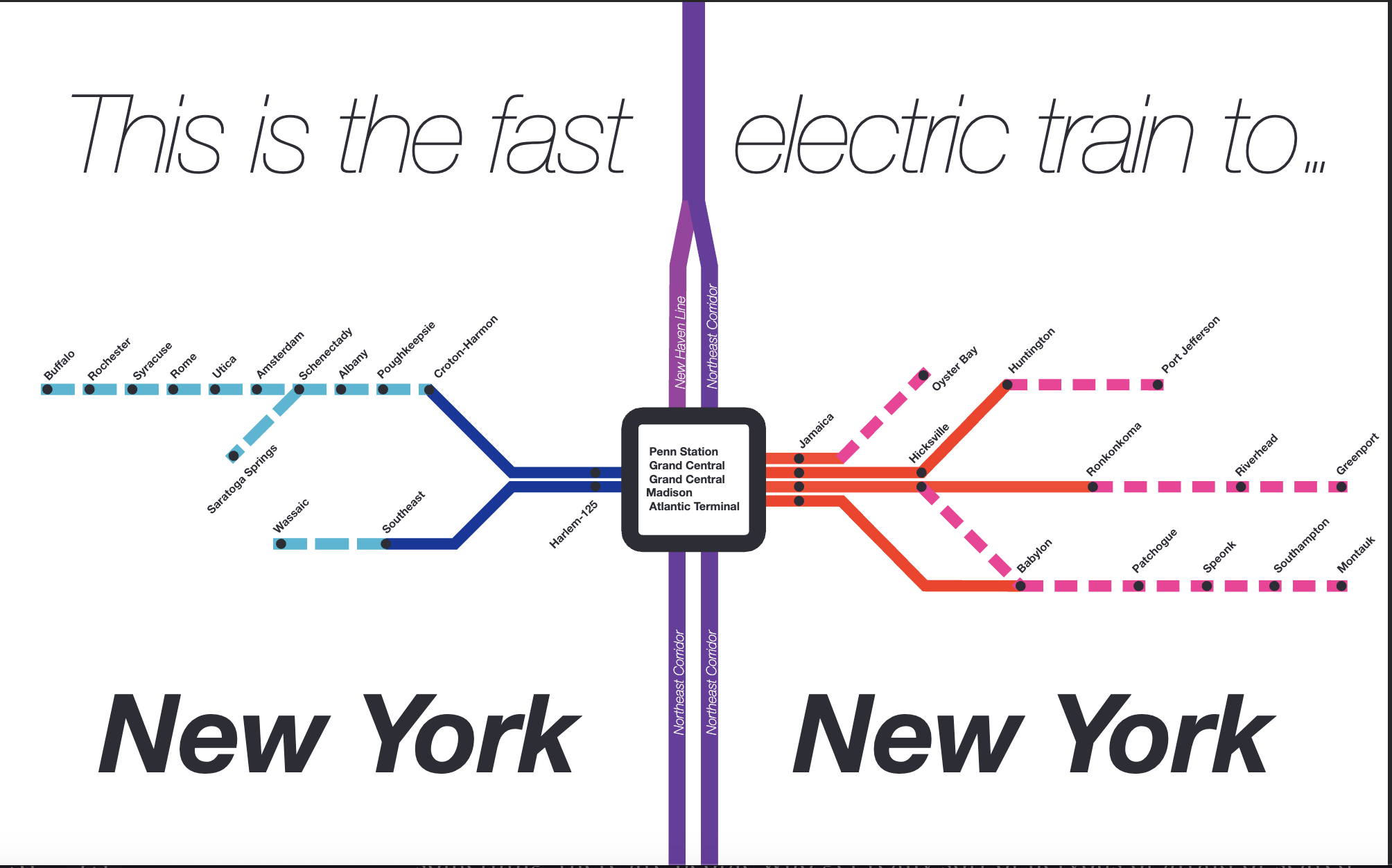

Nolan’s report projects that with minimal changes to the existing systems, the trip-time from NYC to Poughkeepsie could be cut down from 1 hour and 51 minutes to 1 hour and 28 minutes — a difference of 23 minutes that could help turn the Hudson Valley city into a commuter town. It’d cut a half-hour off the trip to Albany, it could take two hours off the trip to Syracuse.

To celebrate Nolan’s completion of the Choo Choo Book and to mark the return of our ability to hang out in person, we rode the subway while I grilled him about Train Stuff. For the sake of journalistic integrity: We met at the Brooklyn-bound A/C/F train platform at Jay St.–Metrotech and took the C out to Utica Avenue before taking the A back to our original station.

Nolan showed up a bit harried after filming a video explainer for Streetsblog. You may have seen his earlier work here, where he explains why New York City’s homeless services team are not quite serving the homeless out at the Coney Island station. It was funny to see him strut down the platform my way. Apparently, he’s the New York institution that doesn’t run on time.

Lindsey: Is this just “Fast Trains for Dummies?”

Nolan: No, not “Fast Trains for Dummies.” It's part proposal and part giant history lesson. We studied a lot of the stuff back in the 1960s and the 1970s, and then we cut a lot of the programs that were funding the research and forgot it all.

Why did you do this project?

I did it because I'm really fascinated and a little frustrated with how little progress has been made with passenger rail service in America in the last 50 years. It feels like we spend a lot of money and we don't see a lot of improvement. So, I was trying to sort of get to the bottom of it

One particular topic you focus a lot of your research on is the use of diesel trains versus trains that run on electricity. Why is it important for systems to move toward electric infrastructure?

It's sort of like the same between a diesel-powered car and electric-powered car. A diesel car, like a Volkswagen, gets decent mileage and has a lot of torque at the bottom, but it's pretty slow getting up to speed, whereas an electric car is like *that* getting up to speed.

Has electrification actually decreased over the last 75 or so years?

It depends on what you mean by “decrease,” but yeah, it has not budged a lot. There are pieces of the American railroading network on the freight side that were electric, that are now no longer electric. But for passenger service, it's basically where it was 70 years ago, with a couple of exceptions.

Why did the Sex and the City ladies take the Jitney to the Hamptons instead of the LIRR?

Probably because there were no seats on the train.

Why are there no seats on the Montauk-bound train?

There's only one track going out there, and they only have so many passenger cars and only so many diesel locomotives. When you combine those things, in total, I think the busiest schedule the LIRR ever gets between the city and the Hamptons on a summer Friday is like eight or nine trains. (I’m doing this off the top of my head.) And they probably need double that number, and then some.

Do you think that reflects well on the LIRR that the Manolo Blahnik women would rather take a yassified Greyhound bus across Long Island instead of the train?

And just like that, it got very real.

I've heard that there's something weird about the track route of the Northeast Corridor. And what's up with the different electrification systems for the Northeast Corridor?

So, that's a legacy of a bunch of different railroads building different pieces of infrastructure that were supposed to be unified and never were because the government cut the money and the other pieces.

Very cool. Can you explain why New York built a brand new train hall that still makes passengers wait until three minutes before boarding to even know which line to stand in to board their train?

Moynihan isn’t a new station. It’s just an annex to the existing Penn Station.

Old Penn Station is between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. Moynihan, which is functionally a new and nicer Penn Station, is between Eighth and Ninth Avenues. But those tracks and those platforms are the same underneath the whole thing.

So, it's the same dispatching program as it always has been. They don't assign the tracks until they know what tracks are empty — and they don't assign the tracks until the trains are moving through the switches. That's why there's, like, three minutes, five minutes notice to come down to the platform.

There's so much traffic moving through the station, and they don't assign platforms to the trains based on schedule. They’re dispatching it all live. It’d be like assigning gates to planes landing at LaGuardia as they’re landing at LaGuardia.

The other reason is they can't board and disembark trains to Penn Station simultaneously because the platforms are so narrow. The trains can only go one direction at a time because of how narrow the stairwells are and how narrow the platforms are. There's not enough space to have 500 people down on the platforms trying to get on the train while simultaneously having 500 people trying to get off a train.

That’s why Penn Station is the way that it is. There have been a lot of proposals to try and fix it, but it would be a pretty big engineering challenge and it would cost a lot of money.

Pretend I’m not smart—

But you are smart!

Yes, but I want to put in print that I am smart. Explain the pros and cons of overhead wire versus third-rail for electric infrastructure.

It's a lot cheaper to use the overhead wire and the physics mean you can get up to much higher speeds. All the high speed lines in France have overhead wiring. The Northeast Corridor has overhead wiring.

The reason the third-rail system exists is because the very, very, very early days of electrification — like the age of my building where I live, and the age of your building where you live — they couldn't figure out how to get what’s called alternating current to work with the trains in motion. It took them a couple of decades to figure it out.

The third-rail system is like, vintage 1880, 1900, and the overhead wire systems start coming out in the 1900s and 1910s. But the Pennsylvania Railroad System doesn’t get built until the 1930s, so it took them a while to work out the kinks.

Why doesn't Metro North go to Hudson? [Ed note: Hudson is “Upstate Brooklyn.”]

Once you get north of Poughkeepsie, the track is owned by CSX instead of the state. There's an agreement between the state of New York and CSX that was part of letting Amtrak run more service. But that agreement bans commuter service on the line.

It bans commuter service?

Yes, it says that CSX has to agree to any commuter service being run on the line.

So we are stuck with Amtrak to Hudson? [Ed note: This makes the trip expensive and annoying.]

Until someone renegotiates the deal. It’s an agreement, right?

Is someone going to renegotiate this?

In “Momentum,” that's one of the things we said: The state should buy the whole line to consolidate and put everything under the MTA control so that you’ve got one set of people in charge of improving it and running the service instead of the system we have right now, where it's divvied up between a lot of different folks. It's just one of those things, one of those dysfunctions.

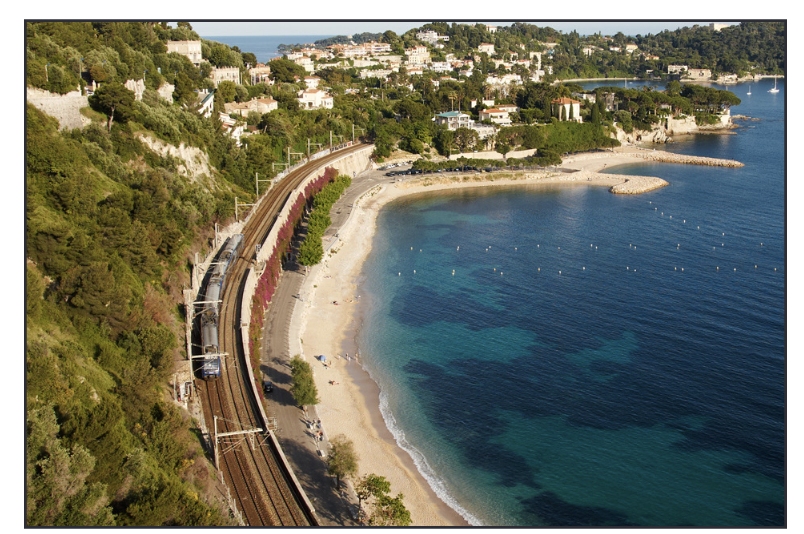

I liked the part of the report where you showed an Italian coastline and compared it to the Hudson River.

Anytime you talk about building something, or anytime you talk about changing something, there are people who get really sort of nervous or afraid or scared about the effects of that change. What I was trying to do there was to show that these beautiful places have great train service.

Train service doesn’t wreck the place. Infrastructure to support the train system doesn’t wreck the place. It’s just as beautiful as it was, but now it’s easier for people to get there.

Here, modernization would make it easier for people to get to Manhattan for doctor’s appointments or whatever. It’s just something that makes life easier, right? We can’t be afraid of making new things. Stasis isn’t enough.

Are you free to hang out with me on weekends now?

Yes.

You can find Nolan at @ndhapple.bsky.social, in the pages of Streetsblog, or on a subway train somewhere. I am very proud of him and his Choo Choo Book, and I hope the people in charge of our mass transit systems put his groundbreaking work to good use.

Critical Thinking is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.