Alone With Joan

If I have no particular fondness for Joan Didion, why did I spend weeks looking through her recipes, letters, and reporting notebooks?

The short answer is that I was looking for a story I could pitch to a major publication. Didion’s personal effects were semi-recently made available to the public at the main branch of the New York Public Library. These documents created a wave of stories that offered a new way of looking at a well-known literary giant. The most significant work to come out from the scavenging of her private belongings is “Notes To John,” a copy of Didion’s therapy journal.

I’ll save you the mystery about how my reporting turned out: No one took my story pitches. By the time I got to the NYPL, American media outlets had reached peak Didion saturation.

The process became the point. I spent long days in a trance, pulling out Didion’s belongings one manila folder at a time. It felt voyeuristic. It was enthralling. The pure dull task of flipping through someone else’s paperwork became sort of meditative for me. Each letter, recipe, or postcard pulled me closer to a literary giant whose status as a cult figure has mostly evaded me.

I spent those days hopeful that I would find some unknown portrait of Joan in those documents. What I found instead was my own feeling of warmth toward a writer whose signature style was to operate at a chilly remove.

“I developed a sense that meaning itself was resident in the rhythms of words and sentences and paragraphs, a technique for withholding whatever it was I thought or believed behind an increasingly impenetrable polish,” Didion wrote early in “The Year of Magical Thinking,” a book I mostly find grating. “This is a case in which I need whatever it is I think or believe to be penetrable, if only for myself.”

There is Joan herself explaining why her work has never taken hold of me the way it has for many, many Americans — especially literary-minded women. Her work is very good. She was a sharp observer of communities where she was an outsider. Her detached style just doesn’t rev my engine, but in these files I learned about the people to whom she was attached.

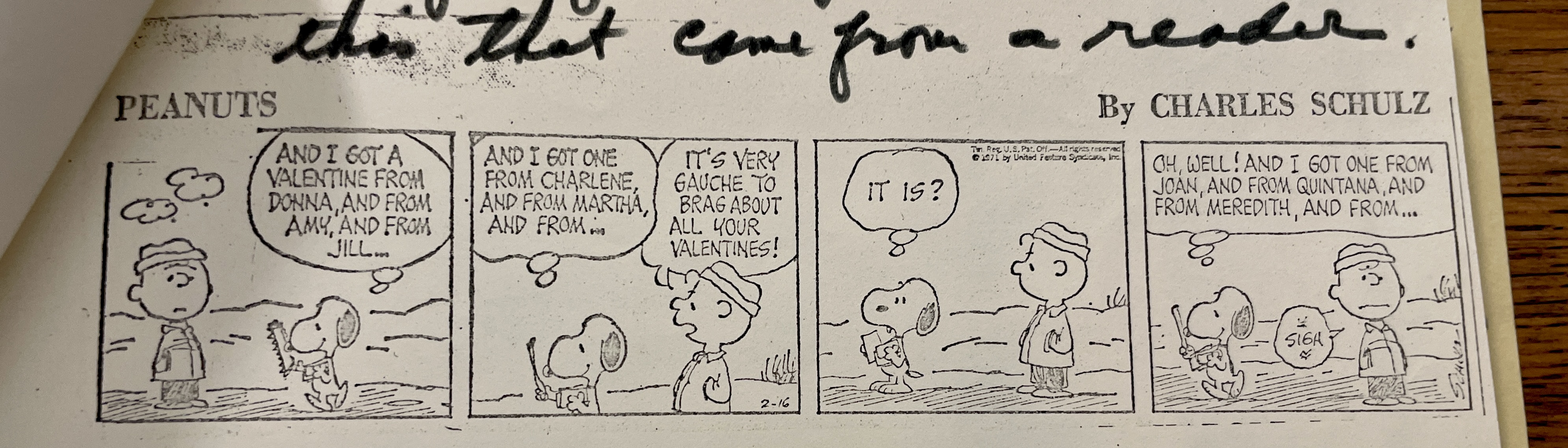

Didion was a generous dinner party host, a person who received fan mail from Charles Schulz and Bret Easton Ellis, someone who documented every dinner with her family. This tiny genius let people in to her veiled life in her own way.

While Didion wrote as a messenger, Nora Ephron wrote as the whistleblower. While Didion explored the development and impact of political factions, Susan Sontag took a torch to foreign affairs. Gay Talese wasn’t always honest, but he brought his subjects to life. Tom Wolfe was a complete lunatic.

It’s fine. I respect and am impressed by Didion’s writing, but it she isn’t one of my giants. My interests are more closely aligned with Sontag’s — probably because I learned them from her.

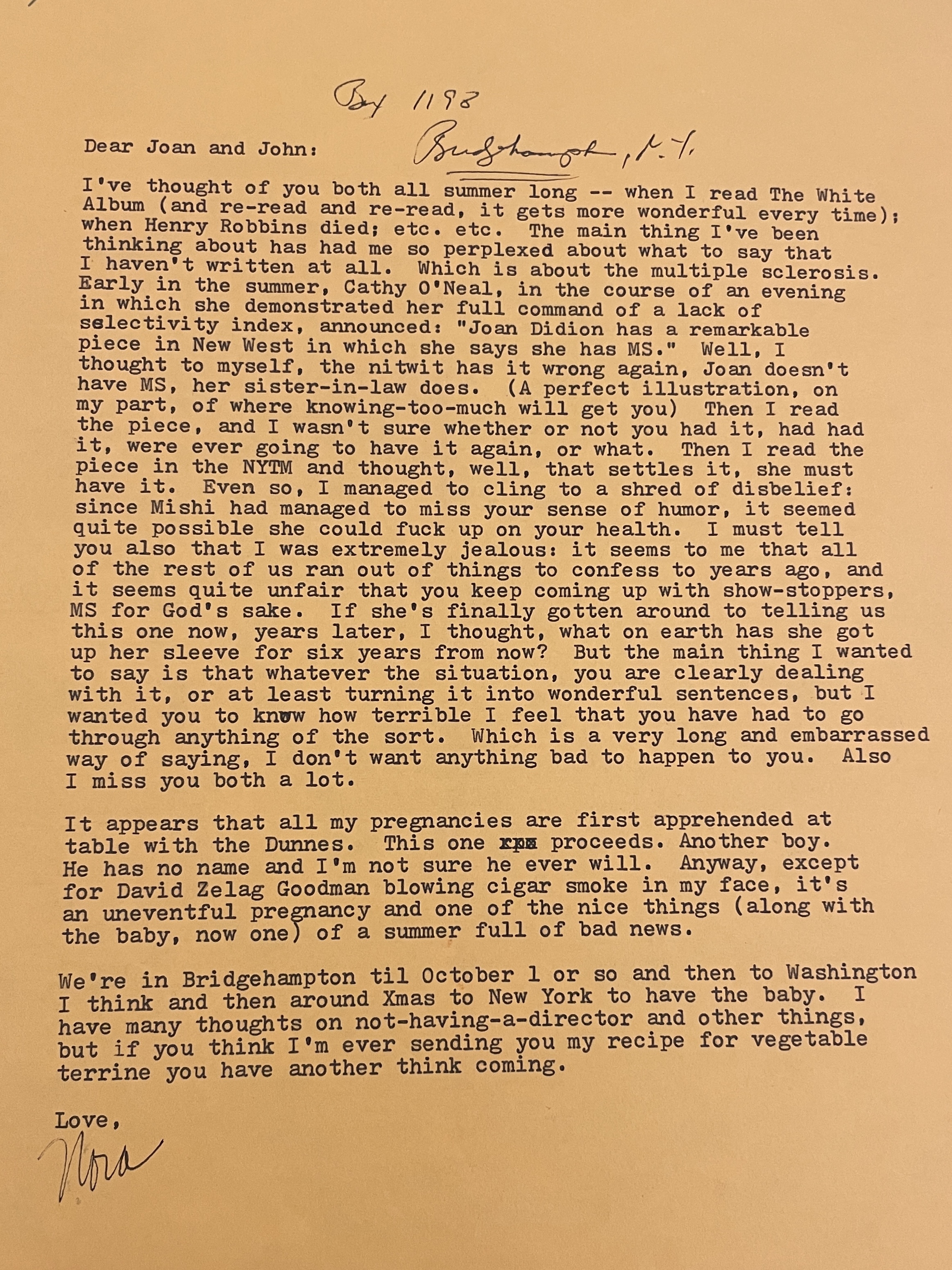

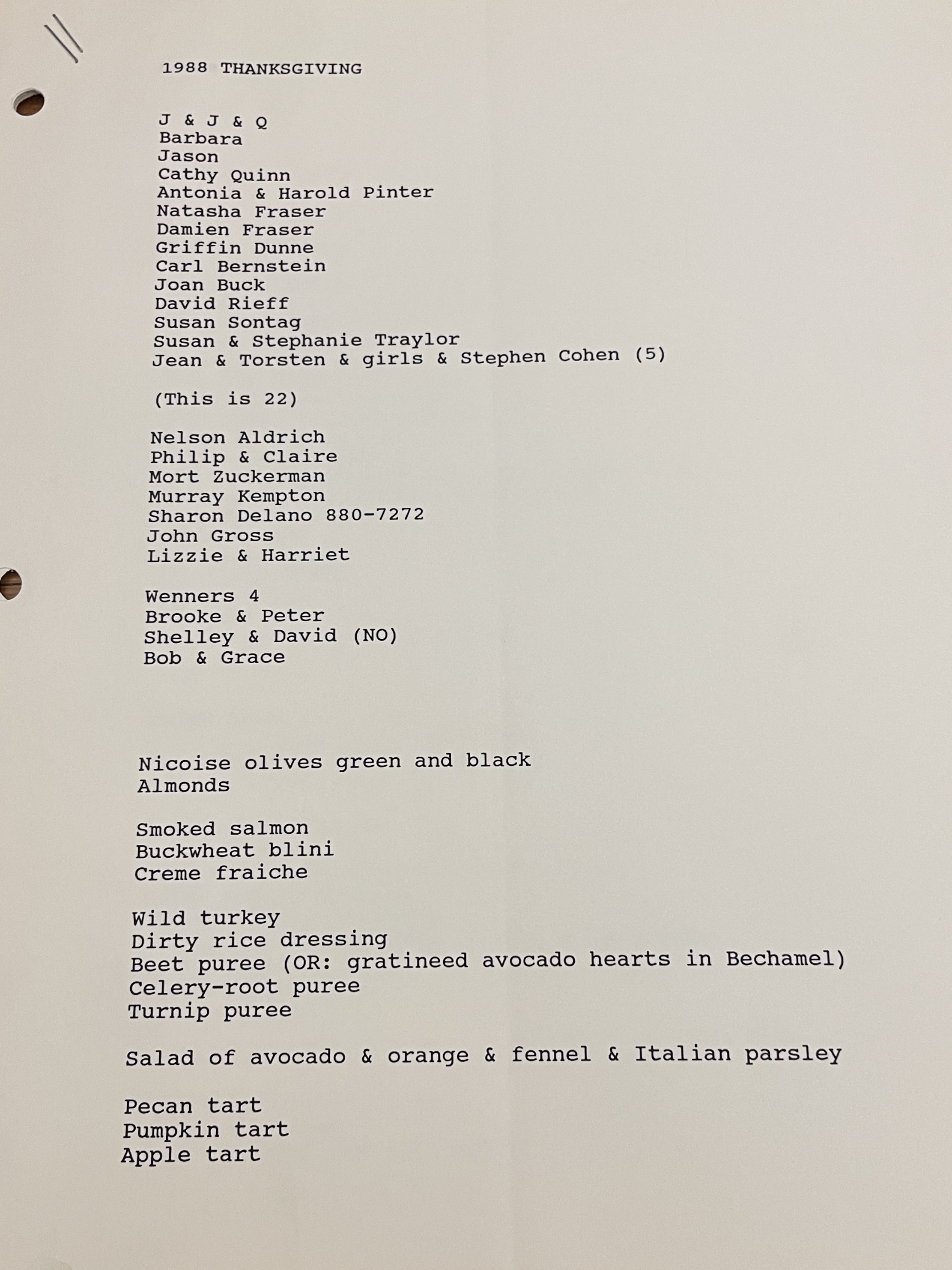

I learned through Didion’s correspondence and party invitation lists that Joan, Nora, and Susan were quite chummy and kind to one another. It was heartwarming.

It was odd to find myself digging through the Didion files. It was a matter of convenience and looking for freelance work, yes, but it was emotionally moving nonetheless. I found myself softening toward this domestic-minded genius. She cared immensely about the people in her life. I just don’t think she knew how to live with the emotions of affection.

It’s a strange experience to go through a dead person’s belongings. My first experience with this was during the Elizabeth Wurtzel estate sale shortly after she died. I purchased a huge framed, wheatpaste-like poster advertising her appearance at a bookstore in support of her book “Bitch: In Defense of Difficult Women.” It hangs in my living room, almost the first thing a person would notice upon entering my home. Bitch! In defense of difficult women!

But obtaining the Wurtzel poster made me utterly damn depressed. I went out to a storage unit deep in Queens and watched a few people pick through Wurtzel’s very aughts-y belongings. It scared me to think of how we are all reduced to our belongings once we are gone. I don’t think Elizabeth Wurtzel was a Coach brand sling bag. I guess I am my Lava Lamp (the non-functional one). Seeing the decontextualized items of her life — online, someone bought her Alcoholics Anonymous chips — just felt like the final tragedy in Wurtzel’s remarkably tragic life.

I’m glad she kept that poster advertising her own work. I’m glad I’m the one who gets to own it. But I will never again buy a dead writer’s detritus.

Didion’s files are a different thing. Her legacy was treated with actual dignity. The Didion paraphernalia is meticulously catalogued and available by appointment only in a small room at the NYPL. Timothy Leary’s are there, too. Susan Sontag’s are at UCLA. David Foster Wallace’s are at the University of Texas. May none of us ever reach the level of literary fame that justifies the publication of our therapy journals.

My initial search of the Didion files was for a catalogue of her books — which isn’t in the collection. I was looking for something specific, something kind of crass. I wanted to know what parenting books Joan Didion read while she was raising her daughter, Quintana Roo. Did she read Dr. Spock? What about Haim Ginott? Did she read whatever was the “What to Expect When You're Expecting” of that era?

I started there because, frankly, she didn’t portray herself as the world’s most adept mother. Her passionate love for Quintana Roo is undeniable. But I found “Blue Nights,” her book about Quintana’s death, to be another instance of behind-the-veil Didionism. She never really explains why Quintana was ill. She didn’t put to page the most painful parts of motherhood and the loss of her daughter shortly after the sudden death of her husband.

I can’t blame her for holding those feelings back, but “Blue Nights” did foment in me a seed of distrust in Didion’s writing. She was the one who told us, prescriptively and persuasively, that applying a cohesive narrative to our lived experiences is a manner of self-protection. But there are certain realities of Quintana’s life that she seemed unwilling to be honest about when she elected to write about her death in print.

My original search was for naught. I don’t know what resources Didion may or may not have utilized to learn how to be a parent. I’m not sure my inferences would have been fair, either. A list of the books in my personal library would make a person think I am much more well-read than I am.

I’m sure I’ll get to all of the unread books someday. And when I die before I do, some stranger will find it fascinating that I own a copy of Carl Jung’s memoir. (To my archivist: I abandoned that one about 25 pages into his descriptions of seeing penises in all of his dreams.)

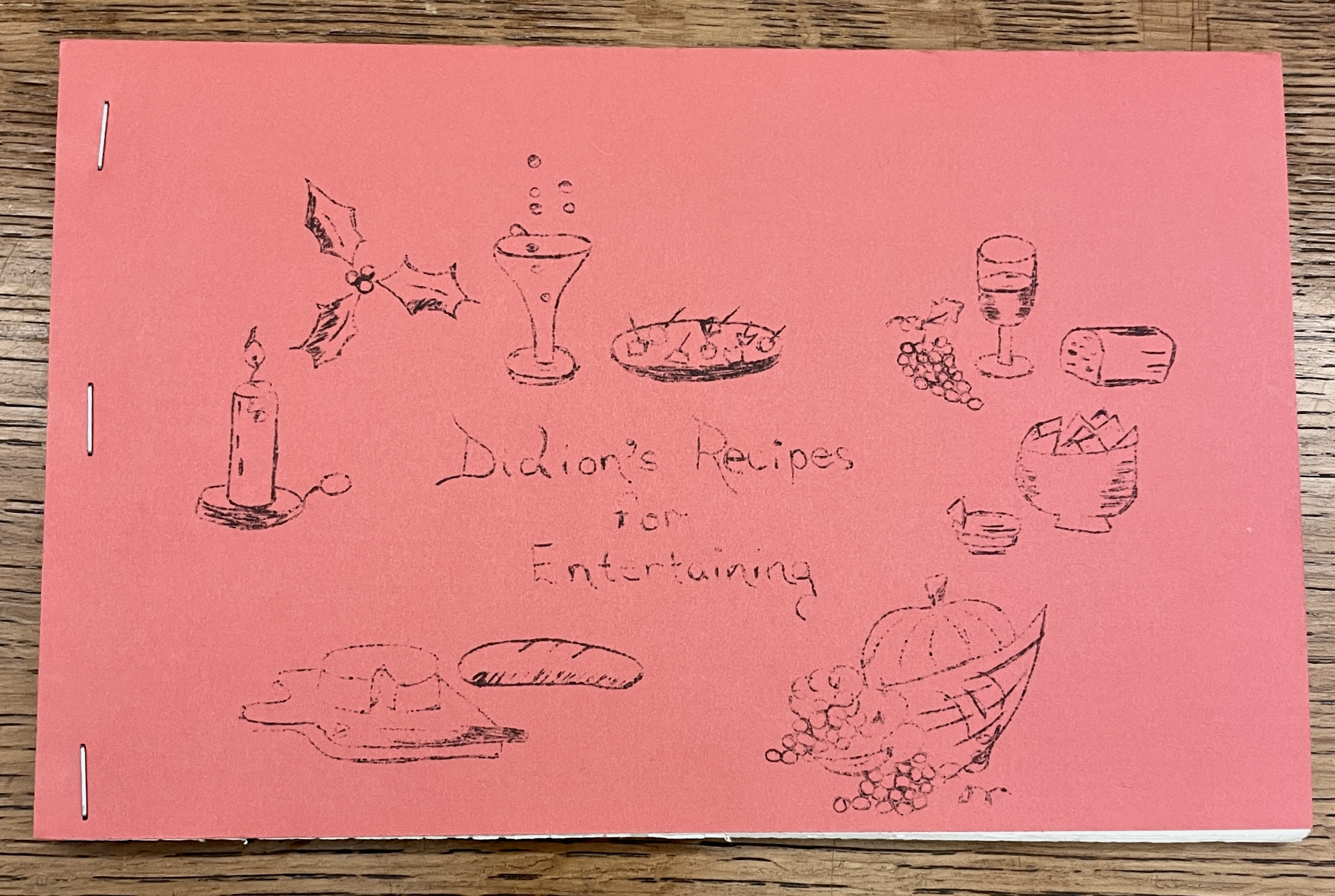

What I did find in Didion’s files was evidence of her ability to connect with her real friends behind the page. I looked through thousands of recipes that she had collected from newspapers and magazines or at the suggestions of friends. Yes, because it was around the 1960s, most of them seemed to be meat goo or fruitcake-adjacent.

Those were the recipes that she noted in one peculiar little journal in which she wrote down details of every dinner she ate that year. Those notes included the date, the courses served, and the guests in attendance. If it was just a family dinner — Joan, John, and Q — they’d still get listed in her notebook.

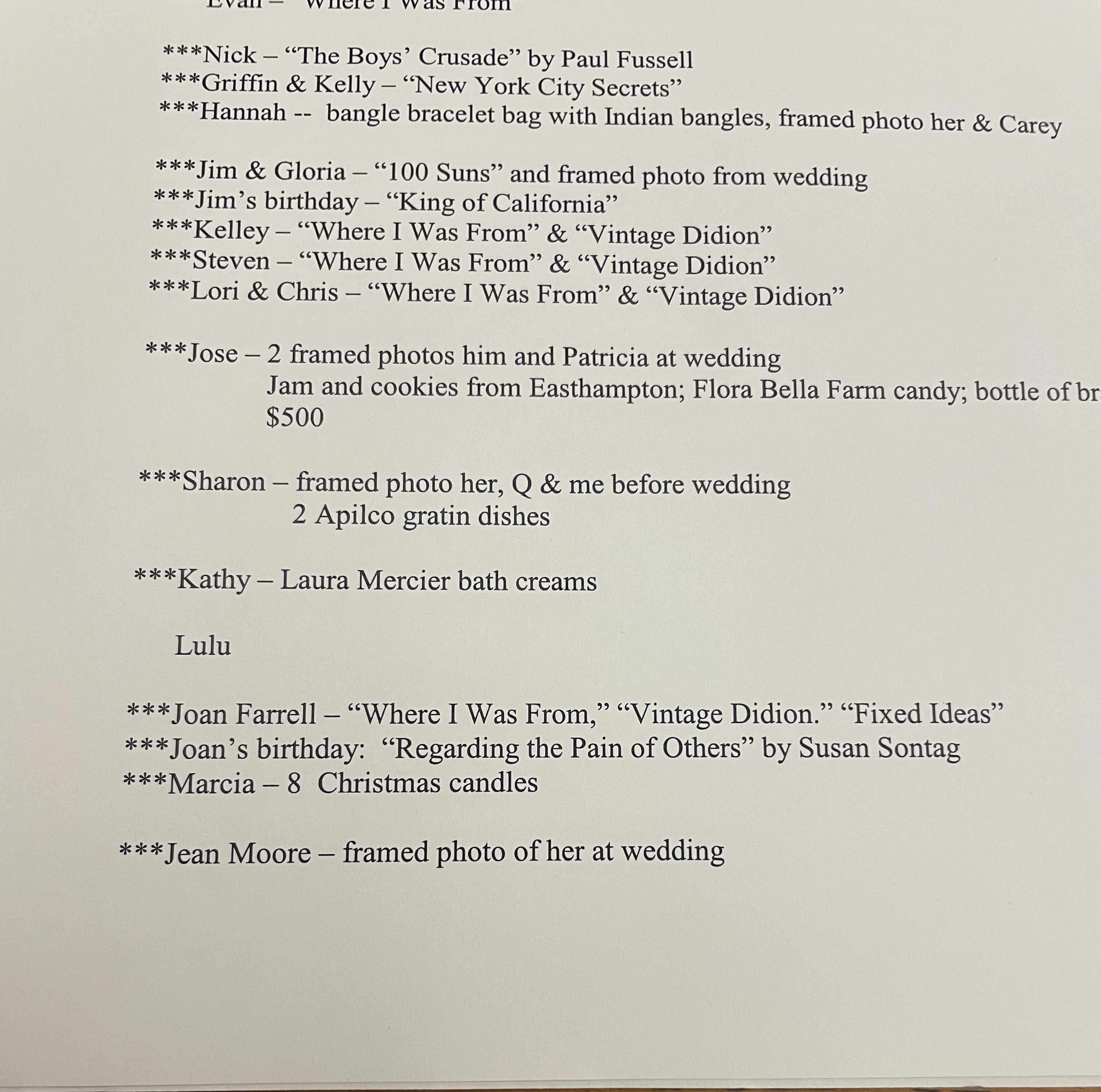

She also used those recipes to throw elaborate dinner parties (often on holidays) for some serious A-list companions. Those events were meticulously documented. Each event had a multi-page list of the following elements: Guests who were invited or attended (and it was noted if they showed up or not), the full multi-course menu, and — if it was a holiday — a list of every gift she gave to her loved ones that year.

I loved reading these party packets. I loved seeing the way she navigated gift-giving. The people closest to her received very personal gifts, obviously. Some years she gave out (what I assume were signed) copies of her latest book to her tertiary friends. I beamed with excitement when I saw that one year, she gave people copies of Sontag’s “Regarding the Pain of Others.”

My strongest pitch to editors came from these packets. I wanted to throw a Didion dinner party with my friends. I knew the menu, had tracked down the recipes, had a sense of the seating, and (thanks to insurance requirements) even knew the shape of her silverware. I wanted to bring her back to life this way — or at least make my friends eat strange foods made with ground meat and gelatin.

No one took the bait. Instead of an assignment, I gained a new perspective on one of the greats.

These dinner files — she kept files on the time she spent with friends! — left me feeling newly tender toward Didion as I wound my way in and out of the historic library. Her domesticity had always been part of my ambivalence toward her, which sounds horrible when I write it in print. But I didn’t like that she was often docile and “John’s wife.” It seemed to me that she dampened her own formidable power. I had no real evidence for this concern; I just knew the long history of women and writing.

I now believe she might have been one of the very few women who could split the existential atom. Didion was not an “art monster,” the term used to describe women who prioritize their creative output above all else. She was also seemingly professionally unhindered by the obligations she made to her family (and friends). This is an outsider’s simplification of the balance of her life, but it is certainly different from the way Ephron and Sontag treated their work and families.

When I had exhausted just about every file in the Didion archives, I returned to reading her work. I saw “Magical Thinking” in a softer light. I felt the same old sting of distance in her essays and reporting. My newfound parasocial familiarity with her life didn’t change much about how I read her work. It just satisfied my long-held desire for an authentic look at the person behind the prose.

Critical Thinking is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.