How to Keep a Journal

A question I am asked often by my friends — including professional writers — is how to build a practice of keeping a journal. Writing in a journal is really one of those top-tier resolutions that people make for themselves but fall out of habit quickly.

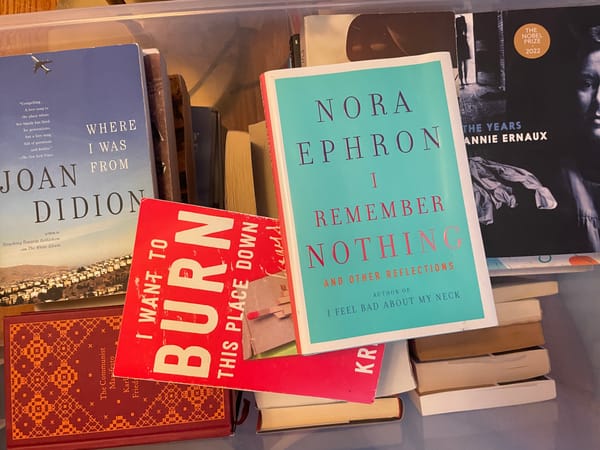

For many years, the only consistent habit I had around journaling was buying a new (often floral) notebook and writing in it for three days before giving up. The optimism was always there; maybe this is the notebook that will help keep me consistent. But no, there is a corner of my bookshelf that is a graveyard for all the small, barely filled journals that I abandoned quickly.

The key to consistent journaling for me was the experience of a difficult breakup that inspired me to make significant changes to my life. I was done with the person I had been to that point, and I wanted to create a record of the hard process of change.

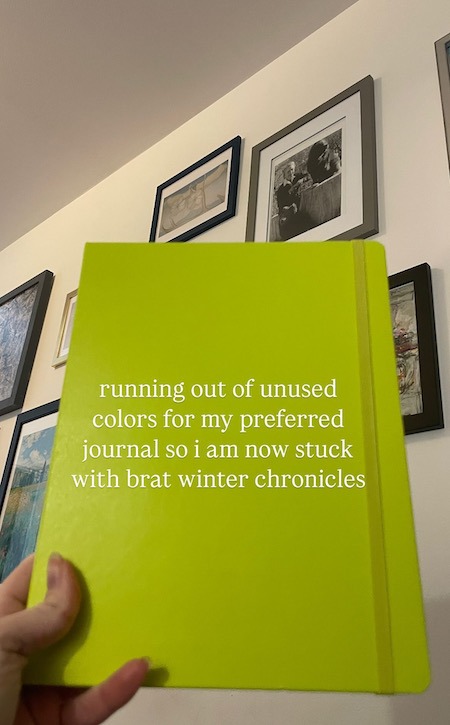

The journal I did purchase for this project turned out to be the full-sized Moleskine hard-cover notebook. There is something funny to me about the common design of journals. They’re made to be small and portable, something that is not onerous in your tote bag. Personally, using the standard sized journal just reminded me that I was trying to journal. Once I made the leap to a full-sized notebook, the practice began to feel like natural writing again.

Journaling is a funny, complicated thing. I have had many internal debates about what to write in my journals and what to do with them when they are filled. Some of my friends burn their journals, which is something I considered at one point. I worried that keeping these chronicles of emotion and self-exploration in my home might be detrimental to my goal of moving forward. I had to make a decision: Was journaling a short-term exercise to help me process an intense and transformative time in my life? Or was it something that I wanted to do for the rest of my life?

I chose to keep going. I write in my journal nearly every day. If you are curious about what is in them (you should be, as I am curious about what others write in theirs), it is mostly pages upon pages of raw emotion and epiphanic thinking. My body (and mouth) tend to burst at the seams with emotion, and I have at many times simply written down a feeling I am experiencing as a way to get it out of my head and into something I can just keep on a shelf. It feels like giving my emotions a place to be permanent that is not the canals of my mind.

Others approach journaling differently. In Benjamin Moser’s biography of Susan Sontag, he points out that she, too, mostly wrote about her own interiority and philosophies of the world, but rarely addressed her real life experiences. I found this to be a withering accusation about the narrowness of the writing she did for herself. Now, I sometimes just write a page or two about how my day went just to insulate myself from the indignity of that disparity.

Sylvia Plath was different, too. She was more of a classic journaler, writing down mostly the experiences of her life — things like “today I cooked a chicken” — from the time she was young. In doing this, she wrote a quasi-biography of her own life. Plath wrote about what happened, but Sontag wrote about how she — funny enough — interpreted her place in this world.

“I feel a sense of mastery, amid all the pain and anguish at being abandoned,” Sontag wrote on February 17, 1970. “A breakthrough of intelligence like this — perceptions not only verbalized, but spun out into a long searching, open-ended discourse — makes me know I’m alive and growing.”

(Another fascinating set of journals is the ones kept by Mark Rothko, which his children turned into an anthology after his death. He writes at length about artistic theory, but never described himself as an artist or his personal experiences with that identity. It is philosophical, not personal.)

It took some time for me to learn how to write for myself after spending 20 years writing for public consumption. It started on Xanga, then Livejournal, then Tumblr, and then I became a professional journalist. My compulsion to share my thoughts with the world is undeterred by any sense of humility or privacy. Here I am today, writing publicly about how I write privately.

The early entries in the journals I began keeping in 2023 are amusing to me now. They are written like newspaper stories. They have ledes, themes, and tidy conclusions. I built a career out of writing formally about other people, so I just turned that practice toward myself.

Eventually, the structure and form of public writing melted away. No one is going to publish these Moleskines posthumously, so I felt liberated by writing in whatever way and with whatever intensity I felt. Some of the pages in my journals are just furious scribbles. Others are more like Bart Simpson writing on a chalkboard: One sentiment written repeatedly as an attempt to codify it in my mind.

I worry sometimes, however, that journaling is a stand-in for my habit of rumination. Sometimes I feel that writing out my feelings and experiences is cathartic. Other times I wonder if I am giving them too much importance and weight. This is not your meditative mindset, where the thoughts and anxieties pass through your mind like clouds in the sky. Journaling gives my emotions the gift of permanence.

Despite all of these internal conflicts around the act of journaling, I keep at it. As I change and grow as a person, I naturally feel distance from what I wrote a week, a month, a year before. Yet these out-of-date entries are contemporaneous notes on how I experience myself, others, and the overall strangeness of being a person in the world. Over time, I will never have to guess how I felt when something significant occurred in my life. It says it right there, in messy handwriting and a hard-cover notebook.

Critical Thinking is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.