Materialist

Next week I am doing one of the bravest things a person can do: I am moving from one apartment to another.

This is an objectively positive decision in my life. My monthly rent obligations will be slashed. I’ll live somewhere that is a better social fit for me. I will still be in close proximity to a major transit line. I’ll have a fresh opportunity to find new coffee shops and actually get to know my neighbors.

These things, fortunately, all align directly with my values: Housing must be affordable for people to tolerate its burden, public transit is a miracle despite all of its flaws, and community building is the only way to live.

It is also a miserable moment of staring directly into the heart of who I am and what other, less flattering things I value. Why do I own all of these books? How can one woman need so many clothes? Does everything in my apartment — from the wall art to the silicone sauce stirrers — need to be so meticulously aligned to a certain aesthetic?

This is not just an expensive apartment I’m leaving. It’s somewhere I learned to create a feeling of home.

I moved into this apartment nearly five years ago on a pandemic deal. I’ve lived a quintessential renter’s story in the time since. My rent was a “good deal” when I moved my belongings into an apartment that allowed me to tolerate the multi-borough commute I had at the time while still remaining in proximity to my friends and support system.

The unit is not rent-controlled in any way. Those apartments are hard to find, and I didn’t have the experience to recognize the way my landlord — an impersonal management company — could trap me into staying put but paying more than I could afford over the span of just a few years.

My landlord’s scheme was borderline diabolical. My neighbors in this building have experienced the same thing. Every year when my lease renewal came up, my rent spiked. I had to take something (a Gabapentin, a weed hit) to even open the email and look at my fate. I thought: This is too much money for one woman to pay for a place to live.

Then, I’d start looking around Brooklyn for alternative options. Something decent had to be more cost-efficient, right? Yet I discovered each year that my current apartment was significantly below market-rate for my neighborhood, and just about everywhere else I’d elect to live would cost me roughly the same amount in rent.

Or, at least, the difference in rent was not significant enough to justify the expenses of putting down first, last, and a deposit — along with movers and all of the other various expenses that come along with deciding to live in one place instead of another.

I could have been more expansive in my annual search. But I spent a few years living an hour-long train ride from most of my friends and that was intolerable and isolating. There were cheaper places to be found. But the spiritual cost of moving away from my community would be much higher — and more permanent — than first, last, a deposit, and a mover.

So I stayed. I stayed in my apartment that became more and more unaffordable each year because, frankly, I’d still be financially burdened in a new apartment. Year by year, I had to assess the cost of staying versus the cost of leaving. The stress of this — an unaffordable housing situation without a solution that would significantly alleviate my stress — eventually made “paying my rent” a constant worry in my mind.

It didn’t help that I am a person who believes that extracting money from people for housing (being a landlord) is not an ethical way to procure capital. I am not a person who does well existing in social and economic systems that go against my beliefs, either. This whole “you have to pay to have the right to live with dignity” shit is exactly why I read the books I do, vote the way I do, and choose my friends the way I do. Some people manage to tolerate the systems they despise. I struggle to compartmentalize my values versus the reality of my life that way.

Eventually, the burden of rent — combined with a massive downscale in income — consumed every choice I made. It added pressure to finding more, new work. It made me feel bad about participating in the cultural elements of New York City that make it worth living here at all. It became my sole preoccupation and whittled me down to a person who existed somewhere inside a thick cloud of housing paralysis and insecurity.

I had to escape the cloud. My rent had finally jumped so high that it was financially irresponsible not to find a new place to live. I’d jumped past market value in other neighborhoods. I have to leave my home.

Moving your belongings from one place to another is an annoying logistical challenge. But I believe the real hell of moving comes from the emotional experience of facing all of your stuff, why it got there, and where it will go next.

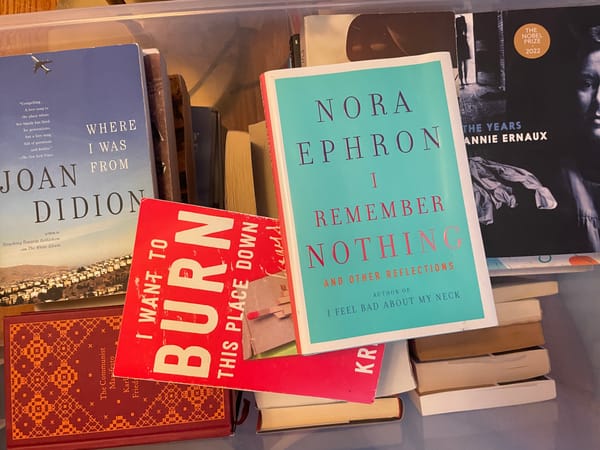

My materialism is slapping me in the face with every closet I open, or every drawer I empty. I own too many books. I own too many clothes. I own too many random things that I remember feeling excited to acquire at the time, and much less pleased to own now.

But when I moved into this apartment, it was essential to me to make my home externally reflective of who I feel I am on the inside. That means being disorganized and cluttered. It also means having framed art on every surface of every wall. In the weeks leading up to my move into this apartment, I studied the frustrating floorplan and created a vision for how I would make my home a museum to the things that I love.

I fixated on bookshelves. I found long shelves that would fit my walls and hauled them and their brackets back from the Lowes in Gowanus or the Home Depot in Bed-Stuy. I spray-painted the brackets on my fire escape. I installed the bookshelves myself (there goes my security deposit). I knew that the first thing I wanted to see whenever anyone entered my home was a wall of books.

I researched storage solutions for all of the clothes I feel I need on hand to express myself in perfect alignment in how I felt that day. I created some damn good gallery walls without measuring the spaces between the frames.

It would have been really nice to have a dishwasher, but aside from that: I had created a place for myself to be me.

Home is a hard concept for me, as is seemingly every basic element of living. Until I moved in to this apartment, I had spent my life to that point feeling either unsafe in my living environment or in a state of transition. I’m weird about privacy in my home to the extent that nearly every single person in my life has commented on it in some or multiple ways. I agree with them that this is not just a quirk, it crosses over into being a complex.

But this is mine. This is me. No one can tell me how to live my life — except for my landlord and my on-the-fritz decision-making processes.

So now, I am giving it up without enough time or energy to grieve that accomplishment. I’ll cry about it in September. For now, I’m taking the arrows to the gut while considering how to organize my belongings into boxes and facing all of the shit I do not need to own.

I’m questioning my need to own all of these books. I spent all of my 20s being insecure about my intellect because I didn’t have the education credentials of all of my peers. (Moving to the East Coast from the West Coast was shocking in that way.) Do I really need to have physical evidence of my intellect? Probably not anymore. But, alternatively, these books tell a story about how I developed my worldview. Is it still so important to me to know how I created the person I am today? Or am I capable of accepting that I arrived at this place and can use many more books (from the public library) to continue that growth and evolution.

And what about my clothes? I purge those more regularly, but external presentation is the only visual art form I know how to create. I can write, but I don’t know how to express myself without words. There’s a deep insecurity about vanity that runs beneath this particular obsession, but dressing myself is a genuinely enjoyable puzzle for me that requires me to take in information about where I will be going and what colors and patterns can be paired in a way that tells an immediate and hopefully unexpected story.

I told an artist friend, sincerely, that my only skill as a drawer, a gradient-maker, or a color-story expert is in how I hold an eyeliner brush and choose my pink or brown powder for the day. We joked that I should just smash my face onto a piece of heavyweight paper. The results would be better than what I came up with during my ten-week introduction to drawing class.

But, along with my intellect, I have to reconsider my relationship to vanity and presentation. Am I the same insecure person I was when I moved into this home five years ago? I don’t think I am. I think I am a different insecure person now. One who, maybe, should make an effort at feeling whole without all of these material items to reassure me of who I am.

This is what I have to put to the back of my mind as I move from this apartment to the next. There’s not enough time now (or ever) to truly consider the significance of every item in my former dream home that turned into an anxiety machine of its own.

Each thing has to stay with me and be accessible at all times, go to a storage unit, or be sent off into the garbage or on the curb for someone else to acquire. It’s not a time to reconsider my values and assess my growth, though there’s nothing that can really make a person confront that more than a physical move from one place to the next.

The boxes have to be filled. The rent needs to be cheaper. The sadness and re-evaluation of myself and my values will have to wait until September. You can find me in a new-to-me coffee shop then, crying silently while reorienting my life and my habits toward an updated sense of identity. The cost of living isn’t punitive enough on its own, I guess. It has to become an emotional barrage, too.

For NYC residents, I recommend choosing Solidarity Movers for this process. Their rates are low, and they actually engage with our community. I never would have thought of “moving company” as part of a broad leftist coalition — but someone has to handle the logistics, after all.