Revolution from Within

In Havana, I discovered a new way in which I am an idiot. An indoctrinated idiot. The worst type of idiot: One who thinks she has educated herself out of idiocy.

A few hours after landing in Havana1, I began to realize that despite all of my knowledge of political theory and the relationship between Cuba and the United States, I had arrived on this powerful island encased in a mental cloud of propaganda.

My efforts to understand Cuba and the threat it has long posed to the existing U.S. political order had only protected me from my own naivety insofar as I knew that I didn’t want to pose in front of a classic car. I knew all about the revolution, I know a lot about JFK, the Cold War is something I relatively understand. I even know about the danger of defections thanks to covering baseball for a few years.

The components are all there! As such, I assumed I was politically informed enough to visit this forbidden country with a sense of enlightenment. Unfortunately for me: no.

The common U.S. perspective on Cuba and its revolutionaries is borne of fear and power — and I found that it had pervaded me, too. Hubris really is the United States’ primary export.

Five days in Havana is not long enough to understand that complicated country and its incredible history of fighting for self-determination. Yet it was long enough to jolt me into clarity on something I thought I’d worked to understand before landing in Cuba: Their version of our shared history is different from what is propagated in the United States.

It was an entirely different exercise to see the country that has so badly threatened the U.S.’s fight against socialism than it is to read about it.

What does Cuba represent, really? It depends on who you ask.

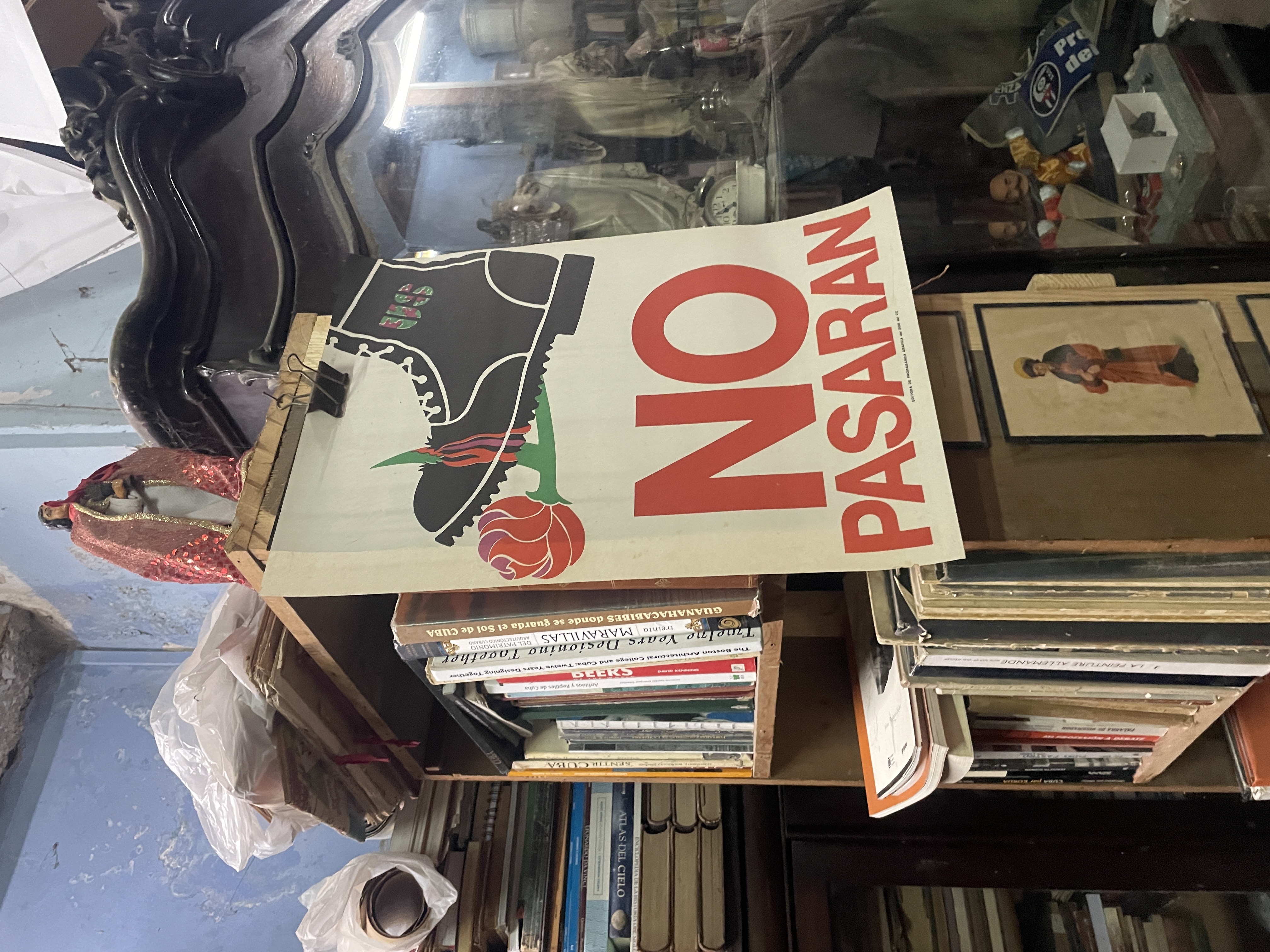

In the eyes of the U.S. hero, our political leaders largely contained the spread of socialism that radiates from the island 90 miles off our own shore. To the Cuban leaders, they were the Davids unwilling to cede their political vision to the Goliath imperialist power that was threatened by their beliefs — and alliance with the Soviet Union.

Further, they resisted letting the United States act with impunity in turning sugar, its most valuable natural resource, into another vehicle for U.S. financial gain.

For the Cuban people, I inferred, it is a society of great resilience with a genuine spirit of community.

That resilience is beautiful and shocking and yet cannot be separated from the ceaseless hardships that befall their society. Is a suffering person who persists in the face of pain an inspiration? Or are they the human reminder of the individual pain that is the collateral of impersonal politics?

It creeped me out to think of all the effort that the United States has exerted to present Cuba as a failed political experiment and cautionary tale. The combination of political rhetoric and restrictions from seeing the island for ourselves has given my country near-total control over the (non-Guantanamo) narrative about Cuba.

But will that condescension ever include a genuine acknowledgement of our country’s contributions to its hardship? The trade embargo is a gigantic red, white, and blue thumb — and the body that bears down on it is eager to show off its enemy’s bruise.

During my few days in Havana, I found my own preconceptions about Cuba arise in surprising forms.

For instance: all around Havana, there are monuments to Fidel Castro’s contemporaries and his heroes. There are monuments to Jose Martí, Che Guevara, and Camilo Cienfuegos. But there is not a single statue of Fidel.

This surprised me. Castro was self-aggrandizing like any authoritarian leader, but apparently he didn’t wish for this to extend to his posthumous legacy.

Before his death, I’ve since learned, Fidel demanded that the Cuban people construct no monuments to him or his brother, Raul.

(One statue Fidel did personally commission, though, is one of John Lennon, who he came to appreciate for his post-Beatles activism.)

But what did this expectation of effigies mean I believed about Fidel, an often tyrannical dissident who also believed in the same political concepts of equality and community that I do?

There is no way for me to have a singular opinion on Castro, whose idealism often failed in reality. He came to power through a visionary uprising, but used that power to break opposition against his own system of government. His reliance on the Soviet Union protected his country and then nearly destroyed it.

Yet I respect his education in Marxist and Leninist theory and the actual implementation of it in his country. His agrarian reform program redistributed land from wealthy Cubans (many of whom bitterly fled the island), but it largely served as a way to kick U.S. sugar mills and its extractive profit system off its land.

But my feelings are further complicated because I don’t know which side’s propaganda to trust. (Neither.) My own country has repeatedly shown that it is an unreliable narrator on foreign governments. Cuba, if you ask the United States, is just another pathetic country that needed to be saved from its leader.

I will reluctantly admit that I found it difficult to mix my hard-left political views with actually seeing the current state of Cuban society.

Aside from what I have read, I don’t have experience to compare the current situation in Cuba to how it has functioned previously — some ups, some downs, I understand. But right now, the country seems politically adrift after the collapse of a potential reconciliation with the United States and the end of the Castro brothers’ long regime. The vibe is, I would say, “not great.”

The bread lines are painful to see. The average monthly Cuban salary is somewhere around 20 USD, according to my Airbnb host. The most common cars on the island are old Soviet-era beaters and few people can afford an upgrade.

Some educated professionals seem to have become tourist hustlers because it’s more lucrative than stable work. In a country whose leaders promised that it would thrive on the basis of community, it appears to be every man for himself.

There was an obvious question that percolated in my mind as I saw the rich history of Havana and the in-your-face suffering of many of its people: How much of this dysfunction is the result of punitive action by the United States?

A lot of it, it turns out. Obviously. My Airbnb host (who won the visa lottery and is now moving to the U.S. later this year) said that from her perspective, the impact of the trade embargo is immense — but that the country’s own political leaders are contributing to the mess. Dysfunction is never a one-party problem, and the Cuban people urgently need solutions from their own government.

Still, it is unconscionable what the United States has done to Cuba, and I felt embarrassed by my country’s successful attempt to squeeze the economic life out of this country to protect its own commitment to a capitalist system. The missile crisis is over, the war against socialism persists.

It took me a few days in Havana to realize that the U.S. embargo on Cuba hadn’t just stopped their people from getting new cars and restricted our access to really big cigars. The embargo — along with the spotty internet access even in Havana — means that information doesn’t really move from Cuba to the United States.

Our messengers, political leaders and an important voting bloc in Florida, have near-absolute control over the United States’ narrative about Cuba.

And mostly, understandably, most people who are too young to have witnessed the actual missile crisis or Soviet involvement have little reason to care about the island and its own history. It seems hardly relevant to our domestic issues (aside from the U.S. military base in Guantanamo Bay). My own interest initially came from writing about baseball.

But it was disappointing to confront what I didn’t know. It was enraging to be amidst the economic ravages of the embargo. It is a country I am eager to visit again, especially when the Cuban baseball league is in season.

Most importantly, it’s a society that I am determined to understand more fully. The U.S. has had a long time to hone its story on the dangers of this nearby island. But the other side has its story, too. It’s simply a matter of seeking it out.

Critical Thinking is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Credit here must be given to Ada Ferrer, whose Pulitzer Prize–winning book “Cuba: An American History” taught me the full history of Cuba-U.S. relations and helped me to reconcile my own perspectives. My deliberate use of U.S. instead of “America” throughout this essay is also a result of Ferrer’s work.

Additionally, anyone who is interested in the topic of the Cuban revolution and the Cuba-U.S.-Soviet standoff is hereby required to listen to season two of the Blowback podcast.

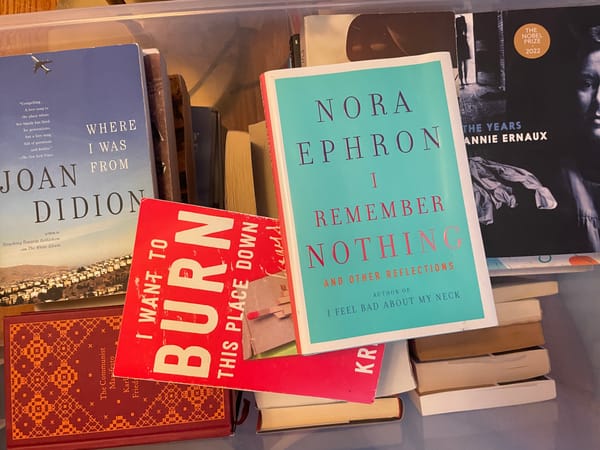

Shout out to Half Price Books for giving me a way to buy an anthology of Jose Martí’s writings without resorting to Amazon. And much love to Tania, my Airbnb host who allowed me to grill her for at least an hour about current Cuban social dynamics and politics.

I was able to go to Cuba by applying for a visa designated for “supporting the Cuban people.” Basically, it just meant that I needed to stay in an Airbnb instead of a government hotel, etc. It was fine and easy. I would love to return and spend more time in other parts of the island, but I do not expect to do so during Trump’s administration. Seems too risky to me. ↩